What does a wooded trail network on conserved land in Stowe have in common with a peak in British Columbia’s coastal range? Both Wiessner Woods and Mount Wiessner carry the name of one of the greatest mountain climbers of the 20th century.

Fritz Wiessner was born in Dresden, Germany in 1900. He became an accomplished climber by the age of 18. Wiessner was influenced by the Dresden climbers who emphasized free-climbing – climbing without aid whenever possible. In his twenties he recorded first ascents on some of Europe’s most challenging cliffs.

Fritz Wiessner was born in Dresden, Germany in 1900. He became an accomplished climber by the age of 18. Wiessner was influenced by the Dresden climbers who emphasized free-climbing – climbing without aid whenever possible. In his twenties he recorded first ascents on some of Europe’s most challenging cliffs.

In 1929 Wiessner moved to New York City and found that climbing in the United States wasn’t as advanced or organized as in Europe. Initially he explored the climbing possibilities near New York City working his way up the Hudson River. Wiessner discovered the Shawangunk Mountains in the New Paltz area making many first climbs. “The Gunks” are now a hotbed of rock climbing and many of the routes still bear the name that Wiessner gave them.

Looking to find more challenging climbs in the Northeast, Wiessner reached out to Robert Underhill, a Harvard professor who was considered one of the best American climbers. Underhill introduced Wiessner to Cathedral Ledge and Cannon Cliff in New Hampshire. On their first visit to Cathedral Ledge in 1933, Underhill showed Wiessner a route that had only been climbed once and represented the most difficult climbs being attempted in America (5.7) at that time. Wiessner led the first pitch with no difficulty, but Underhill wouldn’t attempt to follow Wiessner’s lead. So Wiessner unroped and free-climbed the remaining three pitches with no protection. Underhill knew that American climbing was about to take a major step forward!

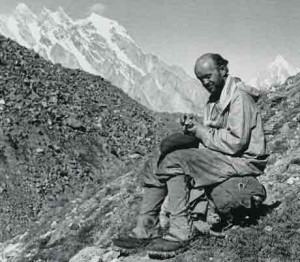

By 1936 Wiessner was taking on major North American ascents. He and a team achieved the first ascent of British Columbia’s Mt. Waddington, the highest peak in the Coast Mountains. A month after that success, he was poised to make the first ascent of the North Face of the Grand Teton only to be beaten by hours by another group of climbers. In 1937 Wiessner recorded the first free ascent of Devil’s Tower in Wyoming.

In 1939 Wiessner led an American Alpine Club expedition to K2 in the Himalayas. They would make it within 700 vertical feet of the summit, but weather and illness forced a retreat and resulted in tragedy with one American and three Sherpas dying. The American Alpine Club placed the blame on Wiessner despite his superhuman efforts to perform a rescue. Experienced climbers of that era disagreed with the club’s assessment, but it still damaged Wiessner’s reputation. Many believe the political climate of the era influenced the club’s findings. Even though Wiessner had become an American citizen, the German connection provided a convenient scapegoat. Many years later (1965) the American Alpine Club would honor Wiessner with a lifetime membership.

In 1939 Wiessner led an American Alpine Club expedition to K2 in the Himalayas. They would make it within 700 vertical feet of the summit, but weather and illness forced a retreat and resulted in tragedy with one American and three Sherpas dying. The American Alpine Club placed the blame on Wiessner despite his superhuman efforts to perform a rescue. Experienced climbers of that era disagreed with the club’s assessment, but it still damaged Wiessner’s reputation. Many believe the political climate of the era influenced the club’s findings. Even though Wiessner had become an American citizen, the German connection provided a convenient scapegoat. Many years later (1965) the American Alpine Club would honor Wiessner with a lifetime membership.

When WWII began, Wiessner supported the war effort by providing technical support to the 10th Mountain Division. This included advice on equipment for cold weather and ski wax! Wiessner’s chemical company specialized in ski waxes including Wiessner’s Wonder Wax! After the war Wiessner would set up a factory in Burlington, Vermont, to produce Fall Line ski wax.

Dean Economou, Larry Heath, and Bill Kornrumpf all named Fritz Wiessner as the founder of Fall Line ski wax.

John Dostal also identified Wiessner, but added that it was “crappy wax!”

Pat Ostrowski heard of Wiessner when Pat lived in Dutchess County and hiked in the “Gunks”. Wiessner’s name was, and still is, well known there. The Fall Line connection came when a mutual friend of Pat’s and mine acquired F. H. Wiessner Inc. in the 1970s. Bob Penniman ran the company and kept us well supplied with ski wax!

My experience with Fall Line wax is more favorable than John Dostal’s. Granted, my usage was primarily on alpine skis, but I liked the wax. The Fall Line product in greatest demand was their cold weather wax. When temperatures were below zero, Fall Line outperformed many of the bigger name companies. How appropriate for a wax made in Vermont.

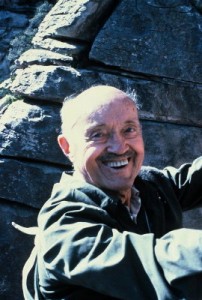

While better known for climbing, Fritz Wiessner was a downhill skier as well. He had started skiing in Stowe even before there was lift-served skiing. In 1952 Fritz moved his family to Stowe. That family consisted of his wife Muriel (better known as Moo-Moo) and their two children, Andrew and Polly. Fritz taught all of them to climb.

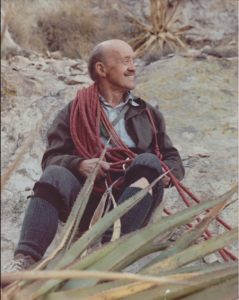

Fritz Wiessner Climbing at age 86 Phot0 By John Rupley

As he got older, Wiessner became a mentor to many young climbers. He was an equal opportunity teacher who encouraged both young men and young women. He insisted on leading the climbs which struck some as being egotistical, but it still provided a new generation of climbers with priceless experiences. Wiessner continued to climb until he was 87, just one year before he passed away in 1988.

The current Curious & Cool exhibit at the Vermont Ski and Snowboard Museum includes Fall Line ski waxes and a life-sized painting of Fritz Wiessner! The painting is on loan from River Arts in Morrisville. Drop by the Museum to check it out. After its stay as part of the exhibit, River Arts plans to auction the painting as a fundraiser.

March 9, 2018 at 11:34 pm

“Although an inspiration to modern climbers, his impact on the 1930s scene is harder to evaluate. In a sense, Fritz Wiessner was NOT an important influence on American climbing in the 1930s, because what he was doing was so far ahead of what others were willing to try that he did not significantly improve the general standard.” -from “Yankee Rock and Ice” by Laura and Guy Waterman c.1993

I love reading about Fritz. What an incredible climber!

Answer – *Bill Briggs*