My junior year in high school my parents bought me a pair of skis. As I’ve chronicled in this column before, buying me a new pair of skis was an annual event since I couldn’t seem to make it through a season without breaking a pair of skis. These particular skis were a pair of Northland Commanders, an entry level wooden ski with screwed-on steel edges and a Ko-Fix base (think P-Tex.) A neighbor of ours had gone to work for the Northland factory in Laconia, New Hampshire, so my parents were able to get a good deal on the skis and bindings.

These skis would be different for me not just because I couldn’t break them, but because they would be the skis with which I made my breakthrough to parallel skiing and they would be the skis that would hook me on the life-sport of skiing. Sadly I did not give them the respectful ending they deserved: I left them in the furnace room of my fraternity when I graduated from college. I had a good job lined up that would allow me to afford far more state-of-the-art skis for the next season.

Norwegians had a long history of handcrafting wooden skis so it isn’t a surprise that they also were the first to manufacture wooden skis. In the late 1800s Norwegian immigrants to the United States brought their ski making skills with them. Many of the first U.S. ski companies such as the Strand Ski Company in St Paul, Minnesota, were started by Norwegians. Ole Ellevold worked for Strand, but thought he had a better way of making skis so in 1912 he left Strand and started the Northland Ski Company in St Paul. A fellow Norwegian, Christian Lund, was also making skis in nearby Hastings, Minnesota. He recognized the merits in Ellevold’s approach and became a major stockholder in Northland. Eventually in 1916 Lund would force Ellevold out and merge the companies in St Paul, but maintain the Northland name. By the 1930s, Northland was the largest producer of wooden skis in the world.

Norwegians had a long history of handcrafting wooden skis so it isn’t a surprise that they also were the first to manufacture wooden skis. In the late 1800s Norwegian immigrants to the United States brought their ski making skills with them. Many of the first U.S. ski companies such as the Strand Ski Company in St Paul, Minnesota, were started by Norwegians. Ole Ellevold worked for Strand, but thought he had a better way of making skis so in 1912 he left Strand and started the Northland Ski Company in St Paul. A fellow Norwegian, Christian Lund, was also making skis in nearby Hastings, Minnesota. He recognized the merits in Ellevold’s approach and became a major stockholder in Northland. Eventually in 1916 Lund would force Ellevold out and merge the companies in St Paul, but maintain the Northland name. By the 1930s, Northland was the largest producer of wooden skis in the world.

Lund and Northland realized that skiing was really a new sport in the United States. As part of their U.S. marketing they produced some very detailed “How to Ski” brochures. In the 1940s these brochures featured Hannes Schneider, arguably the most famous skier of that era, demonstrating his Arlberg technique. Willie White of Waterbury Center has several of these brochures which had been his father’s.

The 1950s and 1960s saw the introduction of new materials in ski manufacturing. The Head metal skis took the world by storm and then fiberglass became a popular choice. Northland had difficulty keeping up with these changes even though they tried. They experimented with metal skis. From the same neighbor that provided the Commanders, I got a pair of demo metal skis. These did everything but turn, and boy, were they heavy! Granted they were seven footers, but really that wasn’t an unusual length in those days. I don’t think Northland ever brought them to market except maybe as boat moorings.

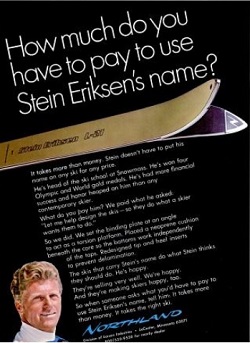

Ad from Ski Magazine November, 1969

In the late 1960s, Northland hired Stein Eriksen to not only lend his name to some Northland models, but design a composite wood/fiberglass ski. But it was the Jean Claude Killy era and Stein didn’t carry the influence that he once did. The skis didn’t sell and in 1970 Northland went out of business.

Bob McKee and David Carter correctly identified Northland as the company even Stein couldn’t save. Bob says he believes he had a pair of Northlands and broke them! Despite my good luck with the Northland Commanders, wooden skis were still wooden skis and prone to breaking. Oh, and the real wooden skis also wore out quicker than most of today’s skis. By wore out I mean they lost their camber. When I abandoned my Commanders, they had no camber – when you put the skis base-to-base there was no visible space between the skis! Which does bring up a question about the new skis: if old skis lost their camber, do new skis lose their rocker?

June 8, 2015 at 3:45 pm

I have a pristine pair of Northland Skylark skis circa 1960’s. They are unmounted and never used. Do you have any resources for selling them?

Thank you

Mary Lou Gavin

June 14, 2022 at 12:37 am

I may be interested. Please contact me

theskisnowman@hotmail.com

Thanks. Bruce

September 7, 2015 at 8:59 pm

Hello Greg. Great reading you piece on Northland Skis. This may sound crazy but i am bringing Northland Skis back as we are producing them in Steamboat with a Hickory core. Of course we lean heavily on new materials and concepts for their performance, we still are making them with lots of camber and sidecut. Get in touch with us as I would like to get you on a pair

Thanks

Peter A. Daley

February 25, 2020 at 7:19 am

Cool! I know of Northland skis through Randy P. in California! A nice article!

December 23, 2016 at 3:01 pm

I found a beautiful pair of blue twin tipped Northland skis. They also have the beautiful leather boots still attached to the bindings. They are about 60″ long and have a black “ebonite” bottom that is advertised on the top of the ski. The most unusual thing is that they have twin metal tips at each end. They are so cool. I’m giving them to my son for Christmas. I have not been able to find any information or photos of this type of ski. I would like any information anyone has. Thanks. Lisa Foster

January 2, 2018 at 1:30 am

Thanks for writing this. My grandfather was the only traveling salesman for all of New England for Northland. He was responsible for getting the factory located in Laconia, NH. I have a lot of Northland items in additions to several “salesman’s samplers” 4 foot skis. Northland dominated the industry for awhile. Great history. Thanks.

August 3, 2018 at 9:13 pm

Hi Deborah would like to talk to you and learn more. We are making a push into the East this year, it feels like we are bringing them home.

970-291-9324

December 7, 2019 at 1:44 am

Hi Deborah,

I am doing a project for Oracle in Nashua NH and they want to do a feature wall with wooden skis. I would love to be able to offer them skis from the Laconia manufacturing plant.

Please contact me…Thank You

July 16, 2018 at 2:14 pm

I too have a pair of unmounted Northland Skylarks (guess they weren’t great sellers!). I’m shipping them to my buddy’s “ski museum” at Pup’s Glide Shop in Breckenridge, where, hopefully, they’ll find a place on the wall.

April 1, 2023 at 6:22 pm

The Skylarks were/are beautiful skis. I think mine lasted 4 days. Snapped a tip carving a turn.

Found a set of new ones, unmounted, factory fresh, they sit in my ski tuning room.

December 18, 2018 at 5:20 pm

Hi Greg,

Bob Bolduc at Piche’s ski shop in Laconia, has a number of Northland skis, including the Stein model. He even has one of the ski making machine from the Laconia factory!

My uncle use to help R&D new skis back in the 50’s and 60’s. I would get my skis from my uncle and learn to ski at Gunstock. I remember well the last ski from the factory ‘Fibotal’ or something like that. It was a black ski similar to Head’s but made with a fiberglass, metal and wood composite. It was not only heavy, it was unresponsive!

I remember skiing with one of the Norwegian engineers. His last name was Jorgensen and was a stylistic skier!

June 22, 2023 at 11:00 pm

Looking for two Northland Ski decals for my old wooden Northlands.

Any thoughts on where I can get thrm?

October 15, 2023 at 1:22 am

Finally, content worth reading. It’s great to find posts like this one.

November 9, 2023 at 6:09 am

Don’t ever stop trying. Onward!

January 14, 2026 at 1:55 am

I have a pair of Northland Ski’s from Laconia NH.

I need decals and leather straps. The need not be vintage.

Can anyone help me?