Picture from "Come Ski With Me"

Stein Eriksen was a successful ski racer winning silver and gold at the 1952 Olympics which were held in his hometown of Oslo. He would follow that up by winning the slalom, giant slalom, and combined at the 1954 World Championships. After those 1954 World Championships Stein decided to turn professional and cash in on his racing success. This would bring him to the land of opportunity, the United States!

Stein’s first job was to head up the ski school at Boyne Mountain in Michigan. Everett Kircher was the owner of Boyne Mountain and offered Stein $5000 to come to Boyne. Stein said he would come if Kircher doubled the offer. Kircher did double the offer and Stein went to Boyne. That would begin a progression of career moves around the United States. He would direct ski schools at Heavenly Valley (1956), Aspen Highlands (1958), Sugarbush (1964), Snowmass (1967), Park City (1971), and Deer Valley (1981).

Several readers quickly recognized Squaw Valley as the area where Stein had never been head of the ski school. One was Chuck Perkins who had the opportunity to ski with Stein at Deer Valley when Chuck was on the International Skiing History Association (ISHA) Board. Chuck also says that whenever he and his wife Jann are in Park City they make sure to have breakfast at the lodge that bears Stein’s name.

I also heard from George Lengvari who correctly listed all the areas where Stein had been ski school director. He pointed out that Stein had been a ski instructor at Sun Valley after the 1952 Olympics, but never headed Sun Valley’s ski school.

I received a special response from Martha Turek. Her father was in the 10th Mountain Division during WWII. After the war Martha’s father opened the first ski shop in Hartford, Connecticut, and Stein worked there when he came to the United States in 1949. That was before Martha was born, but she remembers Stein, whom she called “Uncle Stein”, visiting them during the 1950s and 60s whenever he was in New England. She last saw Stein when he came east to celebrate Sugarbush’s 50th anniversary. She says Stein “still fondly recalled the times he and my Dad would ski through the back woods of Avon Mountain in Connecticut!”

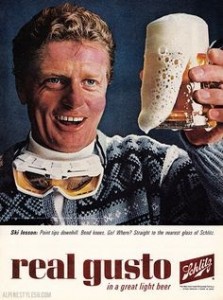

I mentioned last week that Stein became a familiar face in various advertisements. Martha shared a story of one advertising campaign featuring Stein that didn’t last long. Stein did a television ad for Schlitz beer where he would joyfully say “Have a glass of Schlitz!”, but with his accent it seemed to deliver a different message.

A couple of facts I gleaned from Stein’s book “Come Ski with Me.” Stein’s classic flip had its beginnings during WWII when Stein was a teenager. Norway was occupied by Germany and the Germans banned any skiing competitions among the Norwegians. As a substitute for racing, Stein and his friends began to experiment with doing flips on skis. They would build kickers on remote hills where the Germans wouldn’t find them and keep trying flips until they succeeded. Stein had been in a gymnastics program so it gave him some advantages in performing the aerial maneuvers.

Picture from "Come Ski With Me"

After the war, Stein would perfect his flip until it met his standards for gracefulness. Stein’s flip started with a full layout that looked like a swan dive. Only when he was almost inverted would he tuck and then return to the full layout position for the landing. Others may have done more complex aerial maneuvers, but none were as elegant as Stein’s.

Also in his book Stein talks about the skis he used during his competitive years. In the 1954 World Championships he used the same pair of skis for all three events. They were a pair of 220cm wooden skis. He had sets of pre-drilled holes in the skis that allowed him to move the bindings forward for slalom and back for downhill or giant slalom. In addition Stein was way ahead of his time as he modified his wooden skis to have double camber. That is, camber in the tip and tail of the ski, but not as much under foot. He felt the skis held better on ice while still handling softer conditions without catching. So he was observing some of the advantages that we now associate with full or partially rockered skis.

Leave a Reply